© 2014 Thea Summer Deer, all rights reserved

Lycopodium lucidulum

The trail I am following runs parallel to a trickling creek. It leads straight up the hilly cove beneath a canopy of hardwoods and is named the Lily trail. Not named after the fragrant flower but in the memory of a little dog whose name was Lily, a Scottish Cairn Terrier who lived with a friend of mine in this hidden cove.

Alongside the Lily Trail there are statuettes of gnomes, elves, fairies and even one of Lily tucked among the ivy and medicinal plants. The trail was lovingly constructed with wee bridges that cross a spring fed creek. There is even the occasional bench for resting and listening to the sounds of nature and running water. Crystals, mobiles, wind chimes and sun chasers dance from various branches at regular intervals along this magical trail.

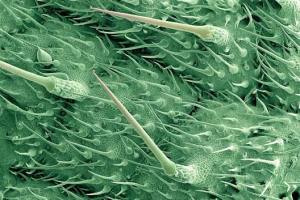

I walked this trail among the woodland flowers, medicinal plants and wild edibles frequently when I lived here in a community affectionately known as “The Cove.” It was here that I noticed the fuzzy, rich green plant known as clubmoss. Club-like it grows in abundance alongside the trail because it likes the moist banks above the creek. I had yet to discover its medicinal value. That discovery began quite unexpectedly when a gardener friend handed me, Healing Through God’s Pharmacy, by Maria Treben. My friend is from England and while she is not an herbalist she grows and uses herbs in the Western European Herbal Tradition for herself and her family.

I quickly flipped through the pages of the book and judged it as being archaic and outdated. I thought surely our current research and understanding of the phytochemistry and active constituents of plants had surpassed the simplicity of this book. So, I thanked my friend and handed it back.

Several months later while house sitting for this very same friend I saw the book on her bookshelf and thought, what the heck. So I picked it up and randomly opened to a page describing the moss-like evergreen commonly known as clubmoss. I recognized it immediately as the same plant I had seen in The Cove. Later, I learned that this book has been translated into 24 languages and has sold over 8 million copies even though I had never heard of it.

I was surprised by what I found there. Published in the 1980’s it wasn’t as old as I had thought even though the information contained within it was. Maria Treben was an amazing herbalist. She was a pioneer of the renewed interest in natural remedies and traditional medicine at the end of the 20th century. This book was a treasure.

Maria Treben

Maria used traditional German/Eastern European remedies handed down by previous generations. These consisted of using only local herbs and diet to successfully treat a wide range of conditions. She used clubmoss to treat cirrhosis, inflammation, and malignancies of the liver. My English friend had been living and suffering with Hepatitis C for decades. I got very excited to think that this might actually be a useful plant for her. So off to The Cove I went to gather clubmoss.

When gathering a plant for medicine I never take more than is needed and always leave an offering. This could be something as simple as a breath given in gratitude, or a hair plucked from my head. In the Native American tradition it is common to leave tobacco or corn meal. Anyone born on American soil is a Native American. So, kneeling down on the soft duff of the forest floor, I offered some hair, knowing that the plant would read my intention and my DNA. Then I gently lifted its trailers with hair like roots from its bed. Mosses have no roots, but this plant I learned is no moss at all. It is an archaic plant over 300 million years old. Club mosses were the dominant land plants during the Carboniferous period and related (as in cousins) to the firs and conifers. Perhaps this partially explains the “archaic” feeling I had when first introduced to Maria’s book.

In memory of Mathabo Photo by Thea

The second time I was called to harvest clubmoss at the The Cove was for a South African friend. Her name was Mathabo and she was a beautiful young woman whose work included teaching women in her village how to become more self-empowered. I was contacted when she began suffering with severe swelling and pain in her liver, most likely from something she had picked up in the drinking water. By the time I was notified and able to gather the clubmoss, it was too late. She had passed away. I was deeply grieved by the loss of this young one. She lacked money for proper medical care and I will always wonder if there was something more that could have been done for her. It is this desire to help alleviate suffering that keeps me walking the trails, talking to the plants and doing the research.

Clubmoss is very diverse and there are two related families, Lycopodiaceae and Huperziaceae. The genus name Lycopodium means “wolf’s foot”. It is no accident that I discovered Wolf’s Foot growing extensively in The Cove, a community based on the teachings of Seneca Wolf Clan elder, Grandmother Twylah Nitsch. How appropriate to find this medicine named for its resemblance to a wolf’s foot growing so abundantly in a wolf clan community.

Clubmoss is a spore bearing plant that grows mostly prostate along the ground with vertical stems up to 3-4 inches high. Hundreds of millions of years ago the ancient earth contained vast forests filled with giant club mosses. They grew to a hundred feet in height and such primeval forests dominated the landscape of earth millions of years before humans appeared. The remains of these giants in their petrified form constitute the fossil fuels of today.

Lycopodium clavatum

The four-year-old plants develop a yellowish spore cone whose pollen is high in sulfur and called lycopodium powder. The powder is highly flammable when mixed in high enough density with air and was used historically as flash powder in early photography. It was also used explosively in fireworks, theatrical special effects and the magic arts. This magical plant that had caught my attention on a magical trail, in a magical cove fully warranted further investigation.

The use of lycopodium powder from the dry spores of clubmoss doesn’t stop with its highly flammable uses. It was also used in baby powders, fingerprint powders and as a lubricating dust on latex condoms and medical gloves. In physics the powder is used to make sound waves in air visible for observation and measurement, as well as to make an electrostatic charge visible. The powder is highly hydrophobic; if the surface of a cup of water is coated with the powder and you stick your finger straight in, it will come out dusted with the powder and completely dry. In 1807 inventors used lycopodium in the fuel of the first internal combustion engine.

While I had long been aware of Lycopodium as a homeopathic remedy, I had not connected it to this plant. Homeopathic Lycopodium is made from the crushed spores and is a remedy used for digestive failure, deep-seated and progressive chronic diseases, liver disease, and carcinoma. This herb has been used medicinally since the Middle Ages and Homeopathic Lycopodium is presently the most widely used form of this plant.

In the Western European Herbal Tradition, clubmoss was used for treating kidney and bladder related conditions. The whole plant was dried, chopped and prepared as an herbal tea. It is a potent anti-spasmodic, sedative and diuretic which makes it useful for treating kidney stones.

As I followed the trail in search of more information on Lycopodium I discovered that it is endangered in many areas and protected in certain states. It is considered as critically endangered in Luxembourg and in the past few decades even considered to be extinct. Some of the reasons cited included; threatened by logging, herbicide application, road construction and maintenance, and extirpation.

This threw up a huge red flag for me. If this plant was imperiled in the Appalachians, why was there so much of it growing in The Cove? What began to emerge connected back to Maria Treben’s book on the healing powers of Lycopodium.

Maria Treben points out that what makes clubmoss such an important ally in treating cirrhosis and liver cancer is that it contains radium. Plants absorb radium from the soil and clubmoss concentrates it. Radium occurs at low levels in virtually all rock, soil, water, plants and animals.

Mountain Top Removal

Photo via the Widdershins

Radon is a radioactive colorless gas that occurs naturally as the decay product of radium. It is in lethal abundance here in Western North Carolina due to our mountain top removals. The Environmental Protection Agency shows a clear link between lung cancer and high concentrations of radon with radon induced lung cancer deaths second only to cigarette smoking. I knew of such a mountain top removal project less than two miles from The Cove. Where exactly was this wolf’s foot leading me? Could the abundance of Lycopodium be in response to the increase of radon: Radon that was being released into the atmosphere from the nearby mountain top removal? Was it helping to bio-remediate the radon? If Lycopodium concentrates radium, what is its relationship to radon? I have not been able to find any information or sources on this subject. Clearly more research is needed.

Marie and Pierre Curie discovered radium in 1898. Marie was the first woman to receive the Nobel Prize in 1911. She was awarded the Nobel Prize for isolating radium, discovering another element, polonium, and her research into the new phenomenon of radioactivity, a word she coined herself.

Once upon a time radium was manufactured synthetically in the US around 1910 and ended up in a lot of products for its purported magical healing properties. Some examples of those products are; chocolate, toothpaste, cosmetics, suppositories, heating pads, wax rods inserted in the urethra to treat impotence, radium water that would cure any number of ailments, and clocks, watches and toys. Needless to say radium got a bad name. Especially when overexposed people started showing up with radiation sickness.

Marie Curie, discovered new elementals.

We live on a radioactive planet and it is well known that if we are exposed to too much or too little radiation, we get sick. Low-dose radiation is documented to be beneficial for human health, but for political reasons, radiation is assumed harmful at any dose. Low-dose radiation has been shown to enhance biological functions with no adverse affects. There are even radium hotsprings where people go to soak for health benefits.

Radon is the single largest contributor to our background radiation dose and is responsible for the majority of the public’s exposure to ionizing radiation. Radon is formed as part of the normal radioactive decay chain of uranium. Uranium has been present since the earth was formed. High concentrations of radium exist in water and air especially near uranium mines. Plants absorb radium from the soil and animals that eat these plants accumulate radium. It may also concentrate in fish and magnify up the food chain. Uranium, radium and thus radon, will continue to occur for millions of years at about the same concentrations as they do now except that levels of Radon have increased due to burning coal and other fuels and now mountain top removal. Long-term exposure can lead to cancer and birth defects usually caused by gamma radiation of radium, which is able to travel long distances through air. How paradoxical that radium gas extracted from uranium ore is used for cancer treatment.

Radium is a naturally occurring radioactive element in the environment and little information is available on the acute (short-term) non-cancer effects in humans. Radium exposure has resulted in acute leukopenia, anemia, necrosis of the jaw, and other effects. Cancer is the major effect of concern. Radium, via oral exposure, is known to cause bone, head, and nasal passage tumors in humans. The US Environmental Protection Agency has not classified radium for carcinogenicity.

According to James Muckerheide in a paper presented at the 8th International Conference on Nuclear Engineering in 2000, he stated:

“Low-dose radiation has been shown to enhance biological responses for immune systems, enzymatic repair, physiological functions, and the removal of cellular damage, including prevention and removal of cancers and other diseases. Research on low-level radiation has also shown it to have no adverse effects. Yet, current radiation protection policy and practice fail to consider these valid data, instead relying on data that are poor, ambiguous, misrepresented, and manipulated.”

Wolf in the Seneca tradition is the pathfinder, the forerunner of new ideas who returns to the clan to teach and share medicine. It is in this tradition that that I share my theory with you about Lycopodium clavatum, also known as clubmoss or wolf’s foot.

“Wolf medicine empowers the teacher within us all to come forth and aid the children of Earth in understanding the Great Mystery and life.” — from Wolf, Chapter 15, Medicine Cards by Sams & Carson.

Thea and Washee

It is my belief that clubmoss made into a pillow and used as recommended by Maria Treben helps to recalibrate and restore the body to it’s natural radioactive frequency in harmony with the Earth. This is Earth-Spirit Medicine, an exciting field of herbal medicine that has appeared on the horizon. We vibrate at a specific frequency creating a resonance and emitting an electrical signal, not unlike those commonly used to keep track of time or to transmit and receive radio signals. The signals that we transmit and receive are part of a grid system that creates a circuit around our crystalline structure. This crystalline structure is part of our Earth and our physical bodies.

“Not really new at all, Earth-Spirit Medicine is being rediscovered at the same time it is evolving to meet our current physical and spiritual needs.” — From Wisdom of the Plant Devas, by Thea Summer Deer

We know that if we are exposed to too little or too much radiation we get sick. When correctly calibrated our cellular structure is restored. I believe that clubmoss restores us to the proper radioactive frequencies. Radio waves, microwaves, EMF’s and all manner of invisible polluting frequencies are bombarding us. If we paid closer attention to the qualities of vibrancy and life-force energy, how different would the choices be that we make with regard to what surrounds us or goes into our bodies? How much closer and in harmony would we be to the frequency of the Earth that heals us and the spirits of the plants that restore us and from which we are made?

How to use clubmoss (Lycopodium clavatum):

Actions: anti-spasmodic, sedative and diuretic

Dosages of different preparations made from the club moss differ and depend on the client.

Clubmoss pillows can be made by filling a small cotton pillowcase or cotton cloth bag with the clubmoss then place over the liver and/or under your pillow while you sleep. This will remain active for up to one year and can greatly help as an anti-spasmodic while recalibrating. It may also help reduce post menopausal hot flashes and night sweats. You can trim off the brown bits that were beneath the ground and while it may seem a bit prickly, when the pillow is stuffed full it will be more cushion like.

Infusion: Simmer 1 ounce of small cut up pieces of the plant (make sure you have a positive identification of Lycopodium clavatum) in one quart of water. Drink one cup per day sipping throughout the day.

Tea: 1 teaspoon per 2 cups of boiling water poured over, steep for ten minutes and drink 2 cups per day on an empty stomach, preferably in the morning.

Homeopathic Lycopodium remedy as directed by your practitioner.

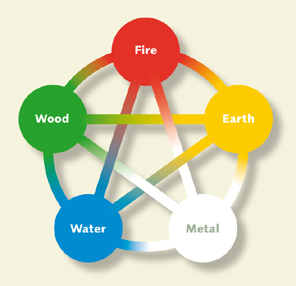

Chinese Medicine: Shen Jin Cao, Property: slightly bitter, pungent, warm; liver, spleen and kidney (Wood, Earth, Water). Action: dispels dampness (Wind), soothes tendons. Indications: weakness and numbness of limbs; traumatic injury. Dosage for topical application is 3-12 grams, used in decoction.

Disclaimer: This blog post does not intend to diagnose or treat. Please seek the advise of a licensed practitioner in your area for any medical related issues. I welcome discussion and feedback, which is critical to ongoing and future research. Please do not ask me to comment beyond the contents or scope of this blog post.

Note: There is another type of clubmoss in the same Lycopodiaceae family growing in the Southern Appalachians and is Appalachian fir-moss, Huperzia appalachiana. Unlike many of the Lycopodium it likes well drained rather than moist soils, direct sunlight and doesn’t creep about over the ground. Appalachian fire-moss is considered imperiled and rare in North Carolina making it vulnerable to extirpation.

References:

Health Effects of Radon: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Health_effects_of_radon#cite_note-USPHS90-1

Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agency_for_Toxic_Substances_and_Disease_Registry

Tell the Truth About the Health Benefits of Low-Dose Radiation, by James Muckerheide, Science & Technology Magazine: http://www.21stcenturysciencetech.com/articles/nuclear.html

Resources:

James Muckerheide audios: https://archive.org/details/TheBeneficialEffectsOfLow-doseRadiation1896-1950.JamesMuckerheide

Radium Hot Springs http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Radium_Hot_Springs